On Wimmin's Land

Five decades ago the heartland of lesbian separatism could be found in the canyons and meadows of Southern Oregon. What does it mean to commit to a radical plan for living?

We came here to create a lesbian universe.

— Hawk Madrone 1

Lesbian Mecca

In June 1982, writer Lee Lynch travelled from Connecticut to the Pacific Northwest to visit a friend, Tee A. Corinne. Corinne was best known for her line drawings of female genitalia, published in 1975 as the Cunt Coloring Book. Lynch recalled, “Tee made several phone calls and out of those apparently uninhabited mountains of Southern Oregon swarmed more dykes that I would see in my first month back [east] … Had I stumbled upon a veritable lesbian Mecca?” 2

As Lynch’s wonder suggests, it’s not common knowledge that for several decades at the end of the last century, Southern Oregon was the heartland of lesbian separatism. 3 Midway between San Francisco and Portland, the region is sparsely populated. A cluster of steep canyons forested with Douglas fir, sugar pine, and Pacific madrone are framed by one wild river to the north, the Umpqua, and another to the south, the Rogue. Tucked among the canyons are picturesque pockets of meadowland. Lesbian locals termed the I-5 corridor that cuts through this crumpled topography the Amazon Highway; they sometimes called the hills “Mama’s Many Breasts.”

‘Nestled in the canyons and meadows was a thriving community of women-owned, women-built enclaves.’

Nestled here was a thriving community of women-owned, women-built enclaves. At the heyday of the movement, from the mid-1970s to the early ’80s, eight separatist collectives flourished in Southern Oregon, with a ninth just south of Portland. 4 Their parcels ranged in size from seven to 150 acres, and were home to anywhere from four to 30 women. Thousands of lesbians visited, from all over the world.

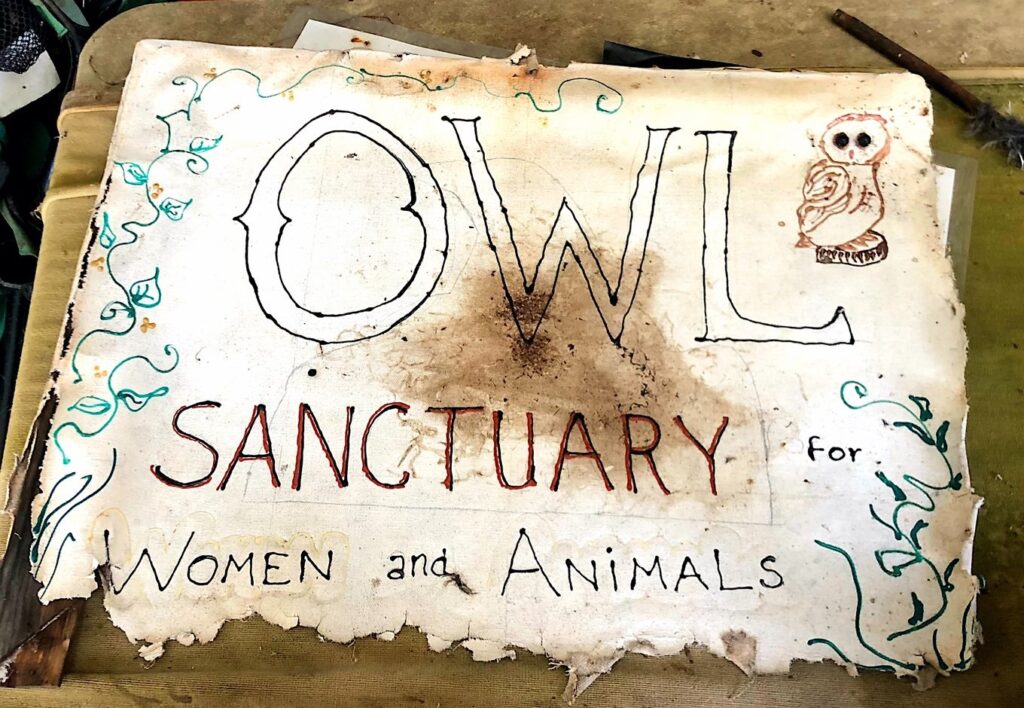

Each land was distinct. Residents at OWL Farm shared meals and a bank account, while those at Rainbow’s End lived more autonomously, each in their own cabins. Fly Away Home sat atop a mountain and Cabbage Lane in a wide ravine. WomanShare was nicknamed “fat city” because it had electricity and hot water. Policies varied regarding marijuana, vegetarianism, boy children, and private property. Attitudes toward policies varied too.

“Separatists cited patriarchy’s voracious appetite for violence — what would now be termed ‘toxic masculinity.’”

To read more, click here.

Notes

- Hawk Madrone quoted in Catherine B. Kleiner, “Doin’ it for Themselves: Lesbian Land Communities in Southern Oregon, 1970-1995,” PhD Dissertation, University of New Mexico (August 2003), 62. ↩

- Lee Lynch, “Introducing Myself,” Just Out (January 1985), 16. Italics original. ↩

- See Ann Japenga, “The Separatist Revival,” Out/Look (Spring 1990). ↩

- This tally is drawn from my research, and that of Sarah Thornton in “’Go West, Young Dykes!’ Feminist Fantasy and the Lesbian Back-to-the-Land Movement, 1969-1980,” MA Thesis, University of British Columbia (December 2018), 2. There were certainly more lands — Fish Pond, Stepping Woods, Kalle’s Campground, Ravensong (aka Rainbow’s Other End), and more. But available records do not indicate the scale or longevity of these projects, and whether or not they were collectives or more akin to private residences. The ninth land, founded in 1973 as WHO Farm, is in Estacada, Oregon. It was renamed Womyn’s Healing Ground in 1986, and eventually became the still-extant We’Moon. WHO Farm may have preceded Cabbage Lane as the first women’s land in Oregon, depending on when one dates the founding of Cabbage Lane. ↩